Research published by Amnesty International in March 2019, The Hidden US War in Somalia, details how 14 civilians were killed and eight more injured in just five of more than 100 strikes carried out in the country in the past two years. These five incidents were carried out with Reaper drones and manned aircraft in Lower Shabelle, a region largely under Al-Shabaab control outside the Somali capital Mogadishu. The methodology used to find and corroborate this research also entailed using Amnesty Internationals’ Digital Verification Corps – which was asked to find any information of strikes it could from online sources. In this post, two of our DVC volunteers from the Human Rights Center at UC, Berkeley, Dominique Lewis and Danielle Kaye, explain how the steps they took to discover some of the the content that helped in this report.

Context: U.S. airstrikes in Somalia

Since President Donald Trump took office in January 2017, United States forces have conducted more than 100 airstrikes in Somalia as a part of its counterterrorism operations against the armed group Al-Shabaab. The number of US airstrikes in Somalia has tripled under the Trump administration.

Amid the increase in air strikes, media reports reveal that the US government has changed its rules on the use of lethal force in counterterrorism operations, effectively allowing US forces to target Al-Shabaab fighters with less regard for putting civilians at risk.

While US Africa Command (AFRICOM) claims that no civilians have been killed by US airstrikes in Somalia under President Trump, media and NGO reports have pointed to civilian casualties.

Amnesty International’s Crisis Response team asked us to use open source investigative methods to trawl social media and gather user-generated content to corroborate information about civilians killed by US strikes. Our open source investigation allowed us to collect information from local news outlets, journalists, and activists.

Methods

Amnesty International provided our team with a list of the dates and locations of potential US drone strikes in Somalia from April 2017 to December 2018, along with the alleged number of civilian casualties and limited information about the identities of those killed. Our goal was to gather news articles and user-generated content on social media platforms, most notably Twitter and Facebook, to corroborate the information provided about each drone strike.

Here we will outline our process for gathering information about an airstrike for which we received the following information:

Date: 2 August, 2018

Region: Gobaale, Beledul-Amin

Further Context: The regional manager of the Hormuud Telecommunications Company might have been found dead.

Preliminary research

Before turning to social media platforms, we conducted general Google searches for news articles about the air strikes in order to begin corroborating the information provided. We also used these news articles to gain more knowledge about the US air strikes in Somalia and the relationship between the US and Somali governments. It is crucial that before we start a project, we have a solid understanding of the situation we are investigating.

For the air strike that was reported to have occurred on 2 August, 2018 in the Beledul-Amin region of Somalia, we conducted a Google search for “U.S. airstrike August 2 2018.” This led us to a timeline compiled by the Bureau of Investigative Reporting that listed a US drone strike that occurred on that date.

The article states that the 2 August airstrike took place 74 miles northwest of Mogadishu, the capital of Somalia. We confirmed that the region of Beledul-Amin — which can also be written as Beled-Amin — is located northwest of Mogadishu.

(screenshot from Mapcarta)

Twitter discovery

After news sources corroborated the provided information about the date and location of the airstrike, we began to gather user-generated information about the strike. First, we turned to Tweetdeck — a Twitter-based dashboard application that allowed us to create search columns related to the strike in question.

Our first step was to create new Tweetdeck columns with time parameters set to 2 August, 2018. We began our Twitter discovery by using general search terms in English such as “Somalia airstrike” and “Somalia strike,” as well as terms from the information provided about the civilian allegedly killed (“Hormuud”).

These search terms allowed us to find a tweet from Mogadishu Update, a self-identified freelance journalist, reporting on the death of a Hormuud employee. The tweet claims that at least two other civilians were killed in the 2 August airstrike.

We also discovered a tweet from Twitter user Halgan Media, an independent Somali news outlet according to their website. The tweet states that two engineers and their driver were killed in the drone strike on 2 August. The tweet cites the location of the strike as Gooballe, which we believe is a different spelling of the village name provided by Amnesty International: “Gobanle.”

(screenshot from Tweetdeck)

Expanding our search terms

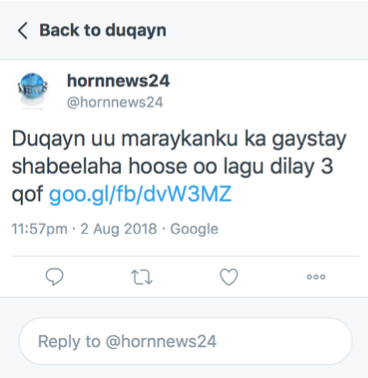

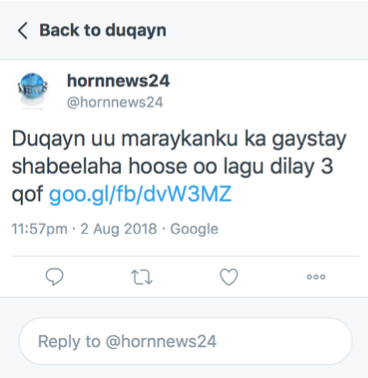

Since using only English search terms excludes a great deal of Twitter content published in Somali, we broadened the scope of our project by using Somali search terms provided by Amnesty’s Somalia researcher. For instance, we searched “duqayn” — the Somali word for “strike” — and came across a tweet in Somali, posted on 2 August, that translates to: “US drone strike killed 3 people.”

(screenshot from Tweetdeck)

This tweet supports the information that at least three individuals were killed in the air strike that was found in previous tweets.

Facebook discovery

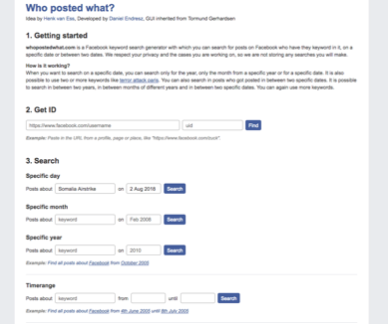

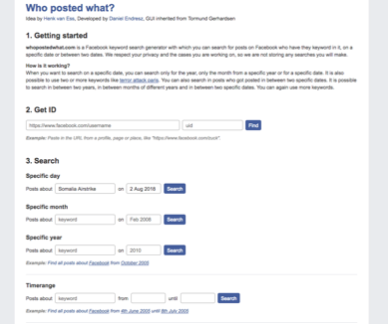

Similar to searching for user-generated content on Twitter through Tweetdeck, we wanted to search for user-generated content on Facebook. However, unlike Twitter, Facebook does not have an advanced search function for their platform. This lead us to using alternative ways outside of the Facebook platform to discover content.

The website whopostedwhat.com is one of the most useful tools to search on Facebook. This allowed us to search all public Facebook posts on a specific day with a key term. Thus, for our strike in question, we selected “2 August 2018” as the specific date and searched “Somalia Airstrike” as the key term.

(screenshot from Whopostedwhat.com)

However, this search and other searches in English did not yield any results. We then began to use Somali key terms, hoping that they would generate results for us. After several failed attempts, we finally had luck with a Somali word for strike “duqayn”. This search term generated one Facebook post that led us to this website that discussed the US strikes in Somalia on 2 August, 2018.

(screenshot from Whopostedwhat.com)

(results from Whopostedwhat.com with search term “duqayn”)

This article mentions that a well-known businessman from the Hormuud Telecommunications Company was killed by an air strike on 2 August 2018. The article also states that the air strike most likely occurred in, or in between, the Goobaalle (potentially another way to spell Gobanle, as previously noted) and Balad-Amin districts. Thus, this article corroborated information about the alleged air strike.

Taken by itself the user-generated information we gathered did not allow us to conclude with certainty that civilians were killed in the US airstrikes, but it did help to support this claim by providing reports of civilian casualties from local sources. And Amnesty International used it as part of an in-depth investigation that went on to unearth credible evidence that five separate US strikes killed 14 civilians, and injured eight more, in Somalia’s Lower Shabelle region.

—

Dominique Lewis is an undergraduate at the University of California, Berkeley (UC Berkeley), where she led this project through UC Berkeley’s Human Rights Center’s Investigation Lab on the Digital Verifications Corps team. Danielle Kaye is a researcher on the Digital Verification Corps team.